Fighting Off The Darkness

Puppetry in Georgia

Budrugana Gagra, hand shadow puppet troupe in Tbilisi Georgia

Georgia, in the Caucasus Mountains, is a country unknown to most people. It is a country about the size of Austria, with mountains taller than the Alps, and they grow oranges there. At different points in its history it could be considered either Europe or Asia and indeed has always been a remote outpost of Orthodox Christian Europe before shading off into various forms of Islam in the Middle East. It was subsumed under Russia 200 hundred years ago and then roped into the Soviet Union in 1921. This leads many to conclude that it is a Slavic culture. But its language is not Slavic, nor is it connected to another linguistic group outside the Caucasus region. Its alphabet is positively psychedelic. The Georgian word for Georgia is საქართველო (Sakartvelo)†, land of the Kartvels. And truthfully Russia is a teenager compared to the antiquity of Georgian culture. The Mongols, the Turks, the Persians, the Arabs, Byzantium, the Romans, and the ancient Greeks all passed this way. The legend of Jason and the Golden Fleece took place in ancient Colchis, which is now part of Georgia. Medea was Georgian woman. Georgia is also the birth place of wine, circa 6000BC. And this is crucial to an understanding of Georgian culture, which still circles around wine in most of its aspects.

Georgia is rich in arts that rarely register outside of the country. Ornamentation is often connected to the intertwining of grapevines. From architecture to painting Georgia has absorbed elements of the civilizations that have passed through, but always modified them into uniquely Georgian modes. In music and dance however their styles are utterly unique. Floating women and impossibly athletic men vigorously dancing on their toes and landing on their knees. Step into a Georgian Orthodox Church today and you will hear gloriously dissonant polyphonic music that reverberates back to the 4th Century, when Georgia became the second country to covert to Christianity. And then there is theatre...

The Horse from the Tbilisi Chamber Theatre’s

Georgian theatre is unique in many ways. They have been influenced by classic theatre and by Russia, but also by the purposely artificial styles of the Symbolists. At a pre-pandemic presentation of Shakespeare's Tempest I noticed a strange thing. No voices ever overlapped. And the rhythms of the speech definitely showed a Symbolist sense of ritual cadence. And these are no mere affectations for the Georgians. In many ways they are a very laid back culture. Time is erratic, some times slow, sometimes very fast. A scheduled meeting might never occur. The traffic is insane. Yet there is one thing that Georgians take very seriously, the toast. At the ritual meal, the supra, each person is required to toast in a thoughtful poetic manner. It starts off with ritualized toasts to God, to families, to women, to Georgia, etc. But eventually one is expected to come up with thoughts from one's heart (guli). And it doesn't go over well if one uses this, the English often do, as a moment for sarcasm. But this ritual aspect of poetic toasting definitely found an echo in the distinctive Georgians modifications to Symbolist theatre.

Likewise with puppetry.

Puppetry in Georgia is both ancient and very new. Ancient, as performed by amateurs in the mountains, where the distinctions between fetish object, doll, and puppet were difficult to untangle. New, because the Soviet Union, as it did in so many countries under its influence, dictated a newer species of puppetry as one of the cornerstones of culture. If one travels to Warsaw one can walk around the Stalinist Gothic Palace of Culture and Science and find massive façades dedicated to Ballet, Opera, Theatre, and Puppetry. It would be impossible to find such a monumental structure dedicated to puppets in Western Europe or the Anglosphere. These were the four cultural pillars every Eastern Bloc country was expected to emulate. Obviously Georgia did the same.

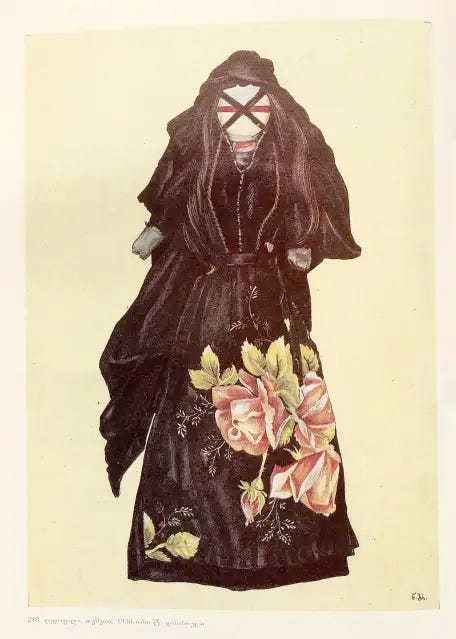

Nino Brailashvili’s drawing of a primitive Georgian doll from Ethnography In Georgia.

Let's look at the ancient roots first. But before we do we have to look at the Georgian word for puppets, which is the same as their word for dolls. The word is თოჯინა (tojina), plural თოჯინები (tojinebi), to distinguish a theatrical puppet they will often use the phrase თეატრის თოჯინა (teatris tojina) theatre doll. They will also use the word მარიონეტული (marionetuli) which can be a specifically string puppet and sometimes is used as a more general term for puppets. And of course there are other words for the different styles of puppets. Also, because of the various regions of Georgia with their dialects and even variations on the Caucasian languages, there also many local names of puppets as well. But the crucial fact is that it starts with a basic mixture of the puppet and the doll. The dolls made here tend to be art dolls with much character. And this tendency goes the other way as well.

The most startlingly unique dolls are also the most primitive. The most traditional folk dolls, called fork and spindle dolls, traditionally were made simply and beautifully with sticks, cloth and sometimes corn silk or even human hair. The dolls had an unusual aura to them, with the face made abstractly out of cloth, buttons, and thread or yarn with an X or a cross for a face. Often the cloth for the figure was embroidered with designs. The faces alone are enough to give a puppeteer many ideas for figures not yet imagined.*

Another of Nino Brailashvili’s drawings from her book, Ethnography In Georgia.

These primitive tojinebi also connect back to a not so distant past where these figures were used in rain making ceremonies. There was one ritual of making the doll, or is it a puppet since these were also moved with simple strings at times, in the form of the biblical Lazarus. Getting the doll wet was an important part of the various rituals. And Lazarus was besought to 'Humidify and wet us.' During the Gonjaoba festival a figure called the Gonja was thrown into the water, while saying 'We do not want hard dried clods of earth anymore. God, give us the mud.' More fearfully there was another festival the Berikaoba, a Georgian version of carnival, still occasionally celebrated in a modern revived form, with strange masks that used to be made from animal skins, particularly pig faces which were particularly used to offend the various Muslim overlords. And there was another related ancient ritual of a person or figure riding a donkey backwards who was then thrown into a river at flood stage. A form of human sacrifice. A form of this can be seen in Tengiz Abuladze's film The Wishing Tree, where a very symbolic figure is seen riding a donkey backwards. And it isn't a good thing.

There was also a figure called Bentera, who was clearly in the lineage of Pulcinella, Punch and Polichinelle. Alas during the course of the Russian occupation of the 19th Century Bentera was enfolded into the Petrushka story, eventually becoming a figure called Petrikela. I can find no one in Georgia who has ever seen a Bentera show. Which is a shame since there was a real puppetry tradition here. Curiously the puppeteers would discard all of their old puppets and bury them, except for Bentera, when transferring their show to the next Bentera puppeteer, the kukne. This echoes the throwing of dolls into the rivers.And this may help to explain why I haven't discovered any images of Bentera.

Also during this era another member of the satiric Punch tribe arrived in the country from Georgia's western side, the Turkish Karagoïz, bringing a shadow tradition which survives in unusual ways. Particularly in the artistic hand shadows of Budrugana Gagra.

One of the other features of these older puppet shows is that they were often performed in a traveling cart called a ბუდრუგანა (budrugana), which would travel from village to village on the rough dirt roads in the mountains. There is a fascinating story of the Soviet Era puppet film animator Karlo Sulakauri watching a puppet show in his village as a boy. When the show was finished and the puppeteers had gone young Karlo was nowhere to be found. He had hidden himself in the wagon and wasn't discovered until many kilometers later. This says something about the nature of these itinerant puppet shows and their relationship to the small villages back at the beginning of the 20th Century.

The first truly professional puppet theatre came about during the Soviet Era in 1934. Founded by Giorgi Mikeladze as the People's Puppet Theatre, later known more specifically as the Tbilisi Giorgi Mikeladze State Puppet Theatre, now more simply known as the Tbilisi State Puppet Theatre. The material performed was of course under serious censorial scrutiny. The influence of Sergei Obraztsov's Soviet approved style of puppetry was felt throughout the postwar Communist sphere. In the 1970s, during a period of loosening censorship Givi Sarchmelidze, as puppeteer and later Artistic Director for the company, sought to open up more Georgian themes, a new approach to set design, and the use of international literature. Sarchmelidze is considered one of the more important figures in 20th Century Georgian puppet theatre. Eventually something like a Georgian style emerged: the use of fingers, the performance on table tops, a modified bunraku technique, actors wearing black behind the puppets, but faces not always covered, rod puppets with short metal rods in the back of the head. Current Artistic Director Nikoloz Sabashvili has taken the company in a direction that incorporates theatrical influences from abroad and more experimentation as well continuing with the children's shows that made the theatre famous.

Tbilisi State Puppet Theatre’s flaming depiction of the city in flames in Sakartvelo.

I watched one production, a play simply called Sakartvelo (Georgia), featured the modified bunraku style not too different from the Gabriadze Theatre. They performed mostly on a table top, with the performers in black moving the figures from behind. The main figures were a wooden donkey and a bird. But whether large cotton clusters for clouds or flat cutout dancers or pails filled with sand and turned upside down, then lifted up to represent an antique sandcastle version of Tbilisi, the sense of invention was continual. The director Niko Sabashvili, coming from the theatre, was bringing to the puppet stage a wider grammar. I was especially impressed when the sandlot Tbilisi was set ablaze, some inflammatory accelerant laced into the sandcastles and then the sandcastles were destroyed with puppet bombs. The donkey and the bird were seeking a butterfly, Suliko, who represented the soul of Georgia. Suliko is also a Georgian song, which is heard several times in the piece. But just when it seems like the butterfly will return it is crushed by the frightening boot of Communism. This reminded me of a Czech show by DRAK called the Magic Bagpipe, asking the question of what will happen to the soul of the country now. But, and this was a similar theme to Budrugana Gagra’s Isn’t This A Lovely Day, the donkey ascends in a ladder into the clouds to find the butterfly in a heavenly place. And then the cast and the audience together sing the song Suliko. And that’s a happy ending in Georgia. Looking forward to eternal life, rather than the life in this embattled world. I find I am often impressed by the deep longings, often thwarted, in Georgian stories.

A similar theme is seen in one of the most unusual puppet theatres in Georgia, a troupe called Budrugana Gagra. Budrugana (the old puppet cart) Gagra (the name of a city lost in the Abkhazian civil war of the 1990s) is a shadow theatre that exclusively uses hand figures. The hand shadows range from the familiar animals to the highly abstract. In one shadow play called Isn't This a Lovely Day?, where hand shadows move to live edited concert recordings of Louse Armstrong and Ella Fitzgerald, and both singers are portrayed as bears, what in America would be an excuse for a bathetic display of sentimentality, here becomes a strangely moving meditation on loss, where the Louis and Ella bears are reunited in death. Which mirrors not only the the donkey ascension of the Tbilisi State Puppet Theatre, but also one of the finest puppet works ever made, Rezo Gabriadze's Ramona, where two trains broken and shattered by World War II are in the end smelted together in a furnace to become one in the after life.

Rezo Gabriadze, whose recent passing was mourned throughout Georgia, and is unquestionably the most important puppet director. Gabriadze was celebrated as an important comedic screenwriter during the Soviet Era. But he turned to puppetry in order to evade the heavy hands of censorship, since puppetry was seen primarily as children's theatre and thus, as in many of the Eastern European Communist countries, was not inspected with the same measure of authoritarian scrutiny as theatre or cinema might be. He brought new respect to the string marionette, which had fallen out of favor in the Obraztsov theatres. He created shows 'too small' for the big stage. His 1996 masterpiece The Song of the Volga, later renamed The Battle of Stalingrad, features the animal perspective of the legendary nightmarish siege. Upon reading a war correspondent's description of the dead and dying horses on the battlefield, Gabriadze said, “The image of that horse on three legs haunted me for a long time. There, in my mind, The Battle of Stalingrad’s theme began to take shape.” Gabriadze could wring deep emotion from his plays.

Georgian puppetry often deals with themes of love, loss, political repression, freedom, and spiritual yearning; mirroring the country's history. Puppet plays or puppets integrated into the performance are also to be found at several other theatres in Georgia. In Tbilisi: The Marjanishvili Theatre, through director Nino Namitcheishvili, will put on several puppet plays in their small theatre upstairs. The Movement Theatre mixes puppets, dance and electronic music (!). And there is a place called Fingers that I haven't been to yet. And Giorgi Apkhazava will soon be opening his Tbilisi Chamber Theatre, which will also feature puppet shows. In Kutaisi there is the Kutaisi Puppet Theatre. The Batumi Puppet Theatre is also respected in that city. Spa towns like Borjomi and Tkaltubo have also had puppet theatres in recent times.

Gela Kandelaki's Budrugana Gagra in Tbilisi is something else altogether. Kandelaki, a contemporary of Rezo Gabriadze, a film director, producer, and actor, who once wrote and directed უბედურება (Ubedureba) a realistic film based on a play by novelist David Kldiashvili. Directing work was not steady under the Soviet system. (Tarkovsky only directed 7 films in his fights with the authorities.) And so in the early 1980s Kandelaki came upon the idea of bringing the old art of hand shadows, which was still performed in some small villages up in the mountains by parents for their children, into a new form. The puppet troupe has a studio in the venerated Rustaveli Theatre. But their performances there are not on a regular schedule But in normal times they perform perhaps once a month.

Many shadow puppeteers make animal hand shadows, as does Gela's troupe. But they also do something quite unique in my experience of various European shadow puppet theatres, they make abstract hand shadows. And they do this often to the music of Bach. In early 2019 they premiered a condensed hour and a fifteen minute performance of Bach's Saint Matthew's Passion in the “small room” of the large Rustaveli theatre. The President of Georgia was in attendance, as was the media. The 250 seat house was sold out. The performance was largely an abstract ballet of hands and shadows. I asked Gela about the spiritual content of his work. The Saint Matthew’s Passion, though abstract, is loaded with suggestions of pilgrimage, prayer, deep beauty amidst struggle. He confessed in my interview with him that though he also said he was not always the most Christian man, something does come indeed through… I think he was being modest. His work has a depth that is quite hard to ignore. When I asked him about the need for puppet theatre in the 21st Century a time filled with prefabricated digital entertainments he replied, “in today's world we are in a spiritual crisis. There are only two possibilities. First, the world will simply crash and disappear. Or, the second possibility, the world will survive. But if we want to survive, we have to go back to spiritual life.”

Georgian puppetry often deals with the hopes that come in reaching out beyond the pain of their turbulent history. Often classic works are reinterpreted in new ways, as in Giorgi Apkhazava's version of Don Quixote. In my 2019 interview with him, in his personally funded and recently created Tbilisi Chamber Theatre, he said that “there are no more living Don Quixotes in this life (time, age), the staff who are making this (new) theatre have a kind of Don Quixote impulse (attitude, motivation), we are fighting at windmills.” And that I think sums up the spirit of puppetry in Georgia today. A kind of quixotic attempt to create something that confronts this uncertain age in a new way. As Apkhazava went on to say, “we have a lack of love today, we are in a very dark period. It can't be darker, it is the peak of darkness. But the darkest part of the day means that the sunrise will come soon. We are waiting for this sunrise.” The 1990s in Georgia during the civl war the darkness was very real, physical, life was difficult, electricity was completely unreliable, poverty deepened across the country. Yet as a teenager Giorgi used puppetry as a way to fight off that darkness. “We were very close to each other. We were fighting together with this darkness. But now it seems so good, so okay.” And yet this glossy life is proved to be an illusion. “And this illusion is in the whole world. It's not just about Georgia. … But the sun will rise.” He pauses, with a thoughtful look on his face, and confesses “I'm too old to give up.” I point out that I am older than he. Giorgi looks at me, smiles wryly, and says “We are too old to give up!”

Byrne Power

Originally written for the Czech puppetry magazine Loutkář and only published in Czech.

July 29th 2021

*There is a book, quite hard to find west of Russia, (both Russian and English text) featuring some of these primitive dolls and lavishly illustrated Nino Brailashvili, from her journeys into Georgia villages. It is called Ethnography In Georgia. It is well worth seeking out.

†Please note I am using the standard Georgian transliterations. WEPA uses the French version even in English.

All photos by Byrne Power unless marked differently.